The Calendar Project

Iconography in the 20th Century. 60 digital prints, various sizes.

Artists: Abeer Gupta, Amit Roy, Archana Hande, Arpita Singh, BV Suresh, Chattrapati Datta, Chintan Upadhyay, Christina Zueck, Deepshika Jaiswal, Kamal Swaroop, Mamta Murthy, Meera Devidayal, Mithu Sen, Nalini Malani, Nilima Sheikh, Paromita Vohra, Vinita Gatne, Vishal Rawlley, Shilpa Gupta, Shreyas Karle, Ram Rehman, Riddhi Shah, Shakuntala Kulkarni, S Basak, Vivan Sundaram, Ranbir Kaleka, Tushar Joag, Sachin Kondhalkar, Sukhdev Rathod, Sudhir Patwardhan

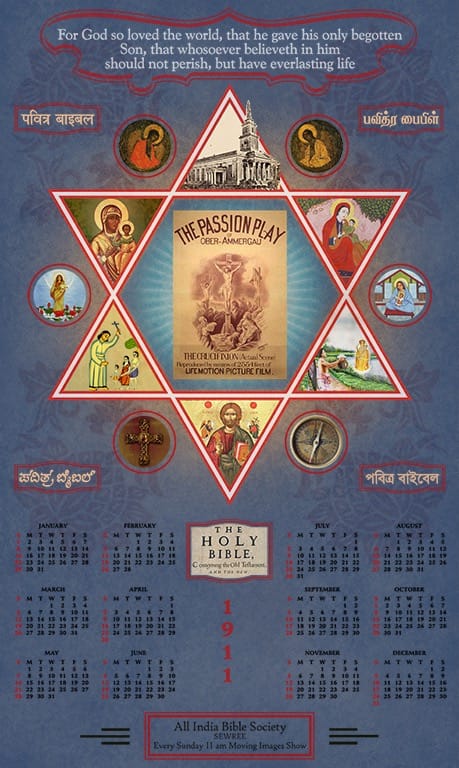

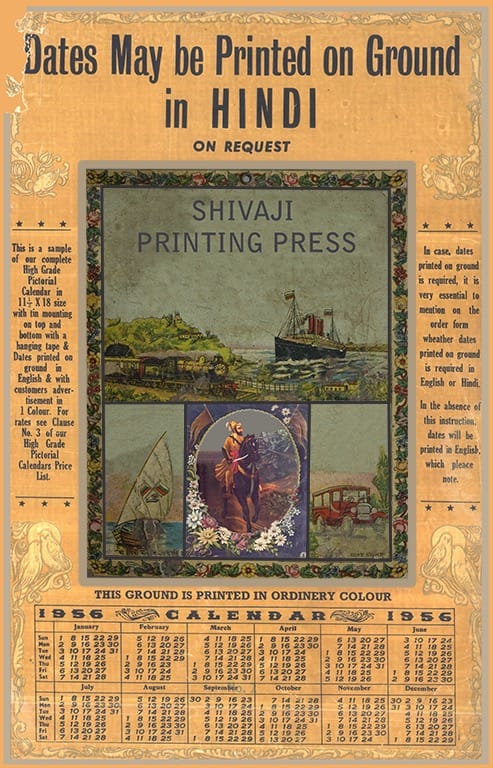

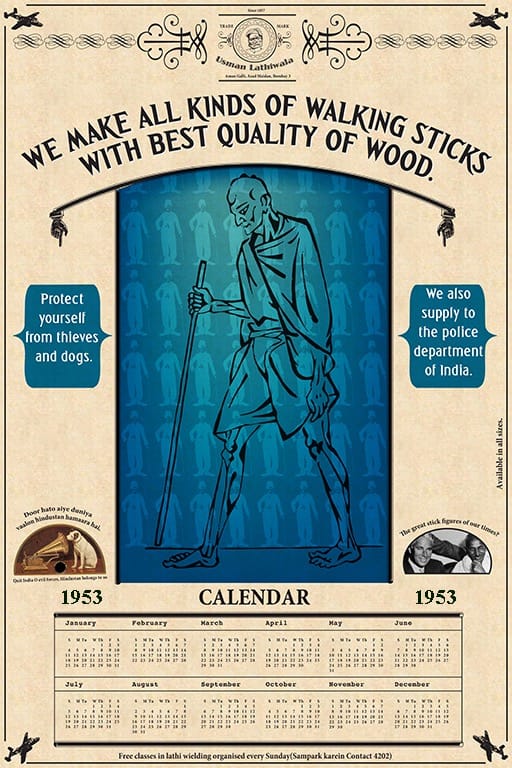

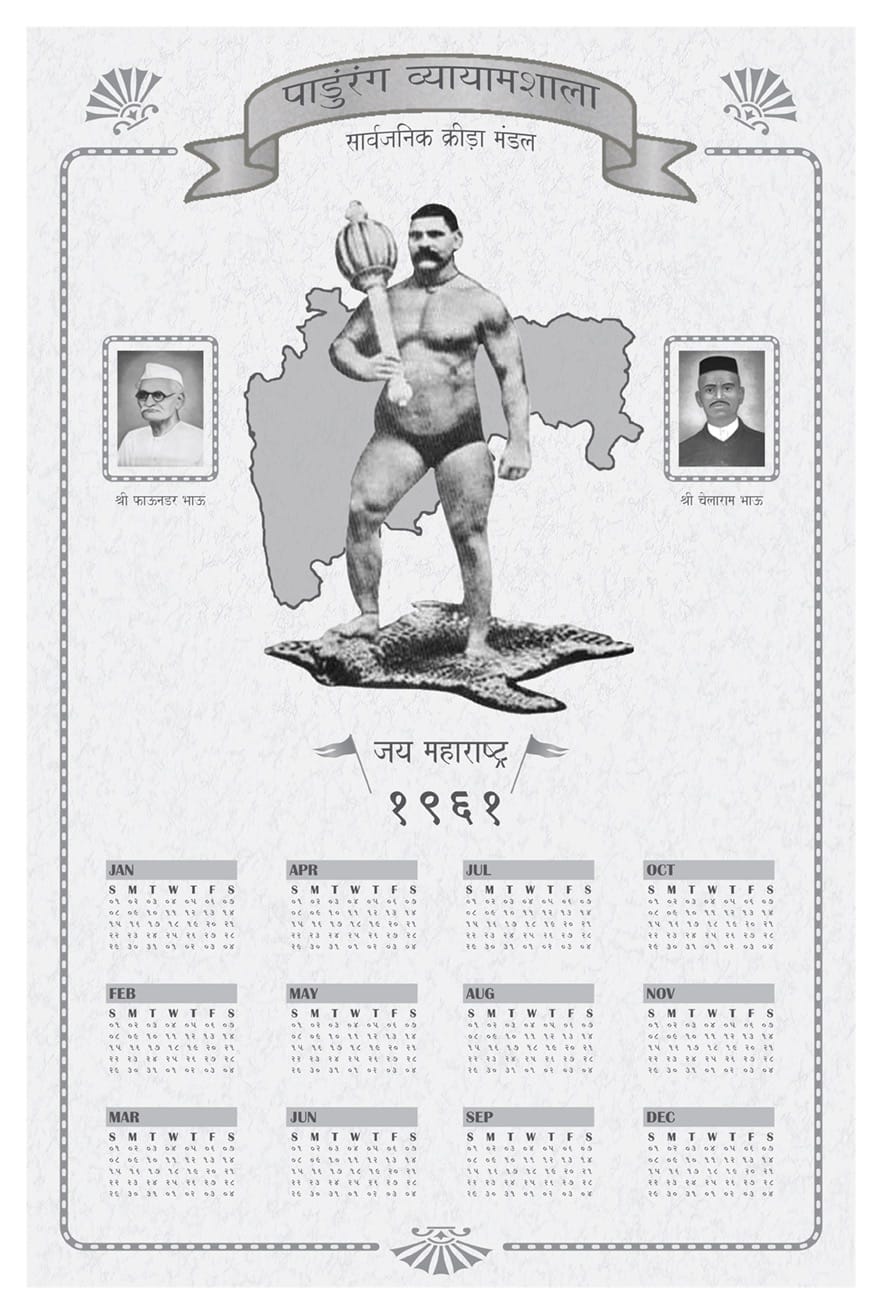

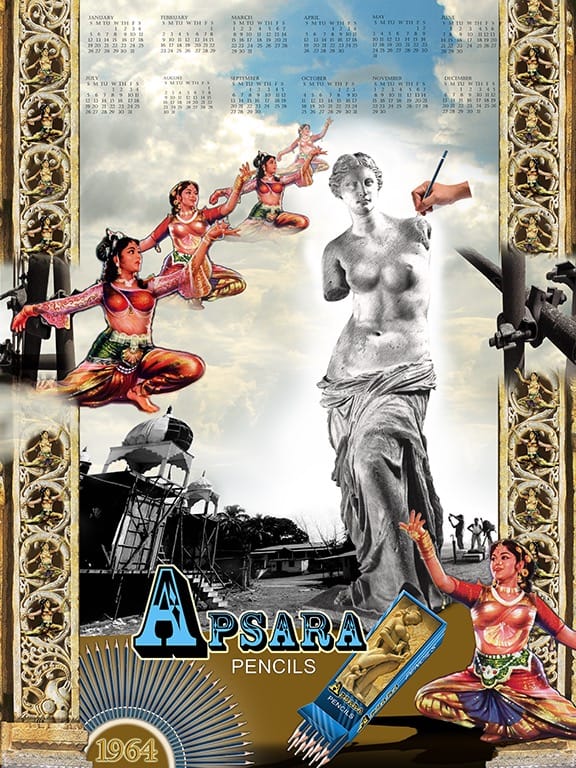

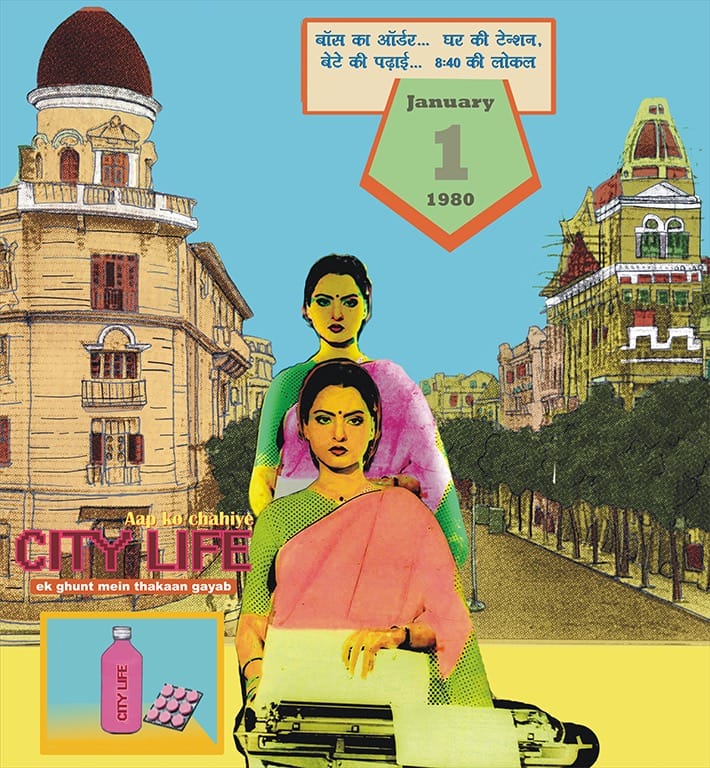

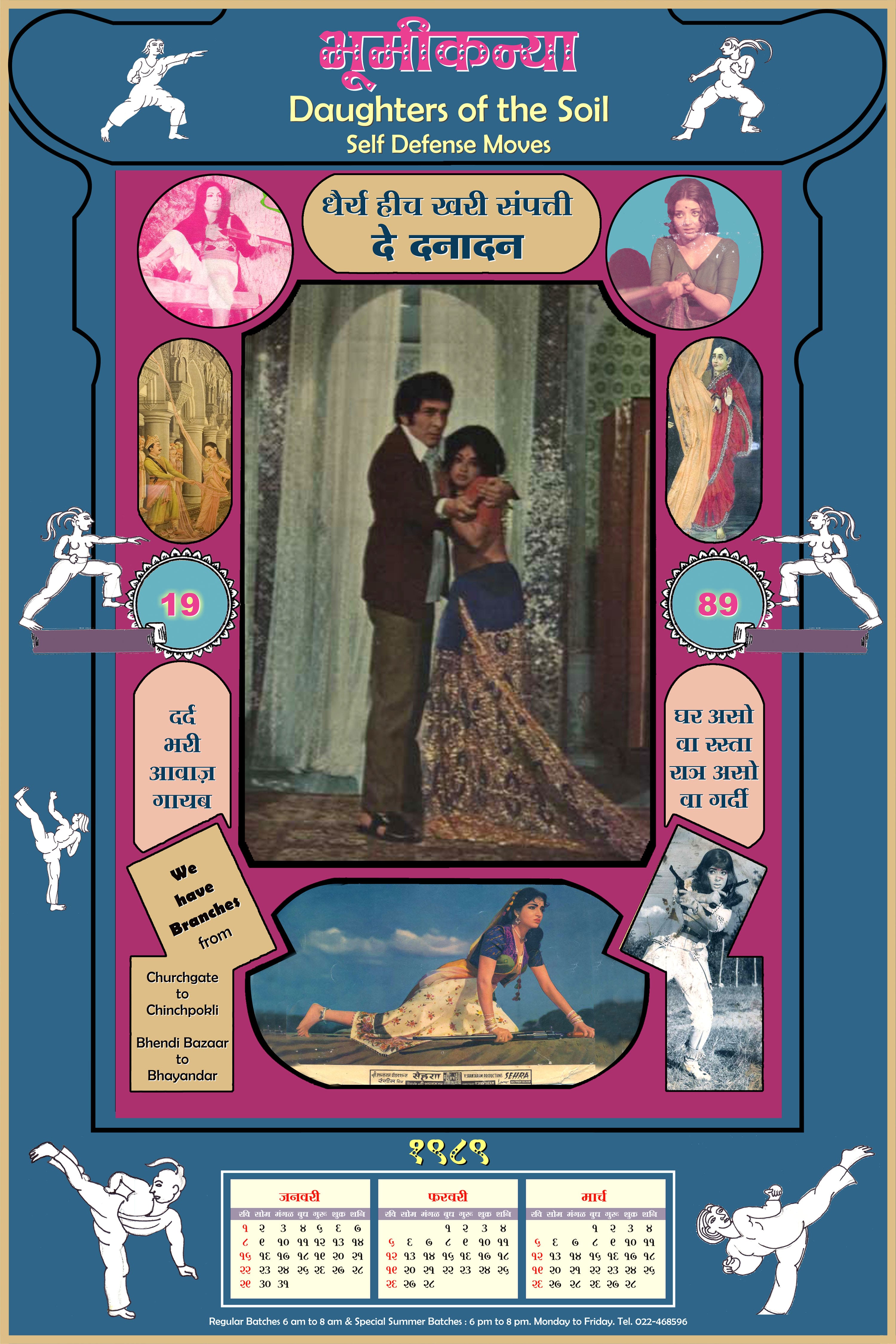

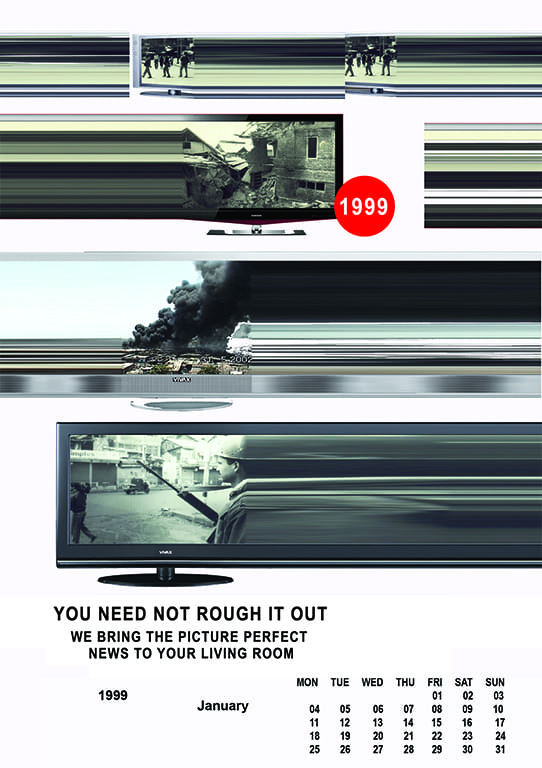

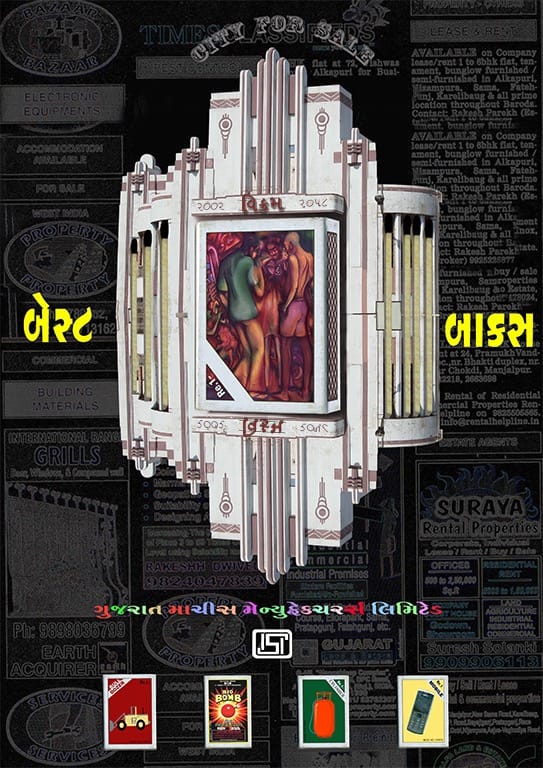

This collaborative project sought to renegotiate the trajectory of iconization

as well as representations and circulation of images in the public domain

through the 20th century. The works were based mostly on found and period

images or on earlier works of the same artists, which are, then, hybridized

through contemporary readings and speculations on the concept of the public and

the popular. Each calendar was of a particular year in the 20th century and

attached itself to a specific commodity or facility. Thus, it simultaneously

created a timeline of public images as well as that of popular commodities.

This collaborative project sought to renegotiate the trajectory of iconization

as well as representations and circulation of images in the public domain

through the 20th century. The works were based mostly on found and period

images or on earlier works of the same artists, which are, then, hybridized

through contemporary readings and speculations on the concept of the public and

the popular. Each calendar was of a particular year in the 20th century and

attached itself to a specific commodity or facility. Thus, it simultaneously

created a timeline of public images as well as that of popular commodities.

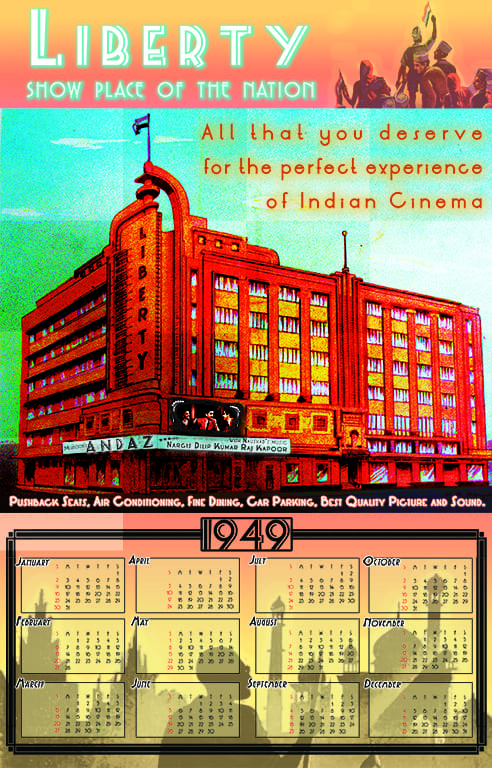

Printing technology and cinema, both with the capacity for multiple and

industrial reproduction, grew in tandem in the early 20th century. Film-based

picture postcards, calendars, posters and monograms became popular commodities

by the early 1940s. Alongside the phantasmic and ever-moving images on screen,

the tangibility of printed images helped consolidate certain image cultures as

public art. Printed products also ensured the presence of cinema in people’s

daily life beyond the time spent in the theatres.

Printing technology and cinema, both with the capacity for multiple and

industrial reproduction, grew in tandem in the early 20th century. Film-based

picture postcards, calendars, posters and monograms became popular commodities

by the early 1940s. Alongside the phantasmic and ever-moving images on screen,

the tangibility of printed images helped consolidate certain image cultures as

public art. Printed products also ensured the presence of cinema in people’s

daily life beyond the time spent in the theatres.

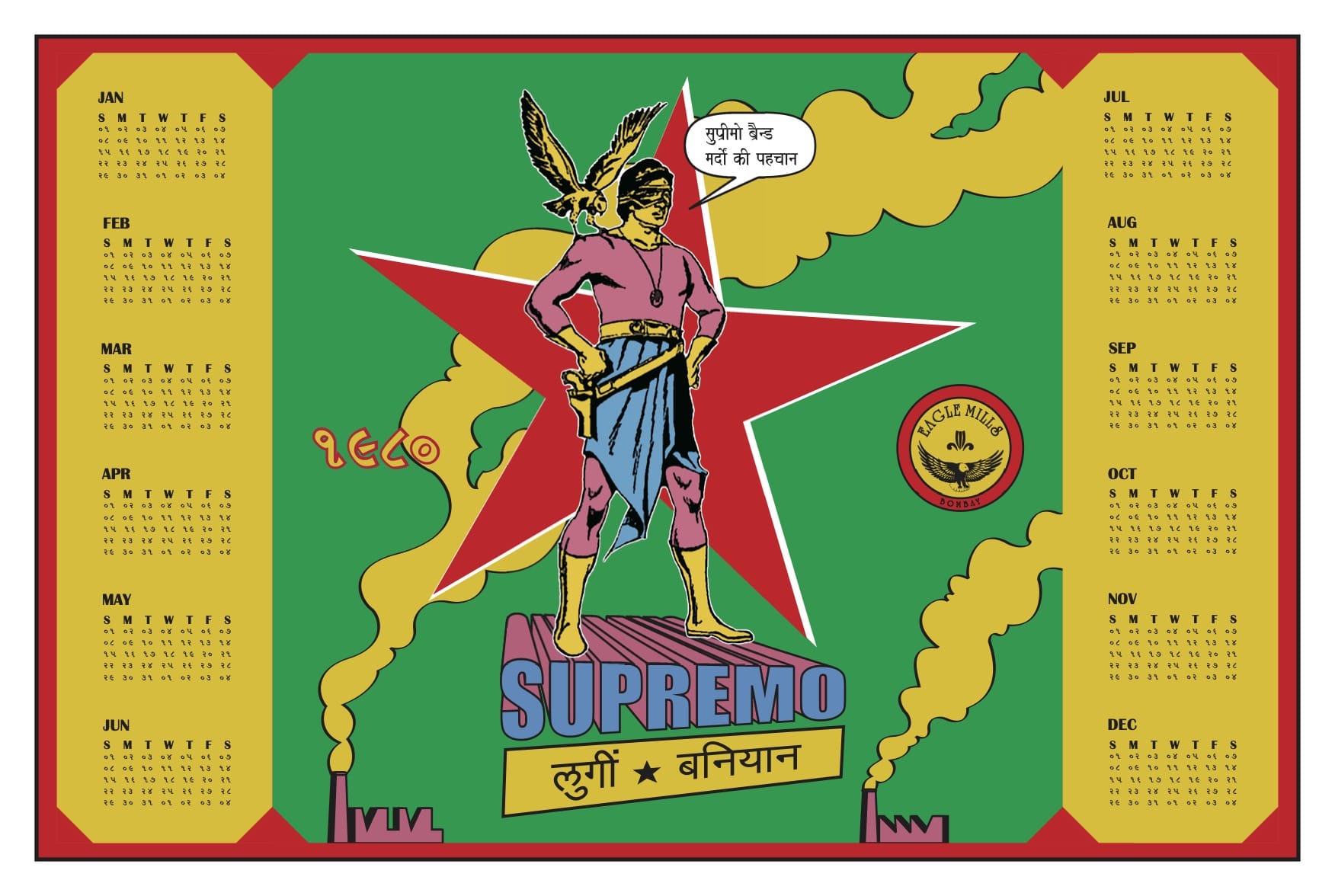

The iconicity of public images, both still and moving, was further enhanced by

the nationalist fervour in the first half of the 20th century. The need for

motifs to consolidate public sentiment around the struggles for independence

and then building of the nation-state, the search for a local film idiom, and

the emerging role of political leaders in the public life - became part of the

developing nationalist culture. Reproducible technologies were strategically

used to meet that outreach agenda. The nationalist agenda, interestingly, was

countered by a growing consumers’ market for foreign goods. Around the years of

the two world wars and the inter-war period, the Indian cities of port / cinema -

Bombay, Calcutta and Madras witnessed heavy traffic of goods and commodities

(including foreign film reels) from distant lands. The commodities needed to

evolve a market, and the market, in turn, needed a visual format and language.

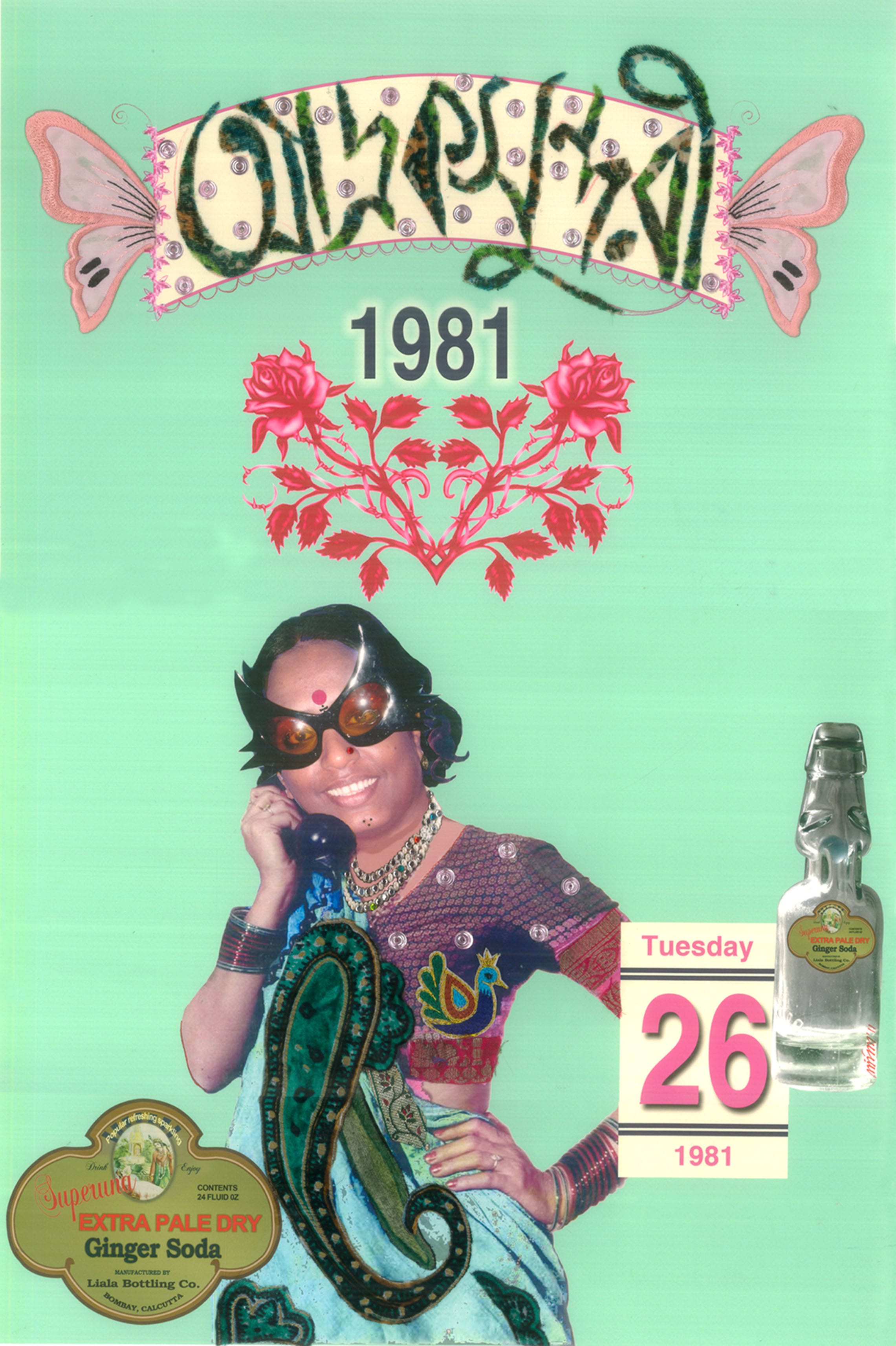

The third strand was the imaginations around an aspirational modernity. Fantasy

images around technologies, commodities, sexuality, wanderlust, life styles,

fetishes etc. were evolved and circulated through printed products. Many of

these complementary and contradictory processes and practices got accumulated

under a broad category called ‘calendar prints’ - women and technology, soap

and nationalism, deities and insurance, Shivaji and chocolate, Raja Ravi Verma

and flying, and so on.

The iconicity of public images, both still and moving, was further enhanced by

the nationalist fervour in the first half of the 20th century. The need for

motifs to consolidate public sentiment around the struggles for independence

and then building of the nation-state, the search for a local film idiom, and

the emerging role of political leaders in the public life - became part of the

developing nationalist culture. Reproducible technologies were strategically

used to meet that outreach agenda. The nationalist agenda, interestingly, was

countered by a growing consumers’ market for foreign goods. Around the years of

the two world wars and the inter-war period, the Indian cities of port / cinema -

Bombay, Calcutta and Madras witnessed heavy traffic of goods and commodities

(including foreign film reels) from distant lands. The commodities needed to

evolve a market, and the market, in turn, needed a visual format and language.

The third strand was the imaginations around an aspirational modernity. Fantasy

images around technologies, commodities, sexuality, wanderlust, life styles,

fetishes etc. were evolved and circulated through printed products. Many of

these complementary and contradictory processes and practices got accumulated

under a broad category called ‘calendar prints’ - women and technology, soap

and nationalism, deities and insurance, Shivaji and chocolate, Raja Ravi Verma

and flying, and so on.

The decades after independence witnessed euphoric emergence of urban-national public culture as well as growing disillusionment over the socio-political conditions. The language of irony entered into the arena of public culture, and, to an extent, challenged the nationalist agenda. Hence the iconisation process was expanded to accommodate the iconoclastic expressions; the popular, occasionally, turned subversive. Around the same time, with the decline of studio system and the beginning of phenomenon of stardom, Indian cinema cultivated the portrait culture.

In the Calendar Project of Cinema City, 66 works were digitally produced by many people - spanning from senior artists to undergraduate architecture students. They are not replicas but re-conceptualisation of the former popular culture in the light of contemporary thinking. The individual works, that may seem inconspicuous as single pieces, attain a special exuberance when collated and placed together. When seen as a series they come to present a refracted/subverted temporality for the 20th century.

Menu

Menu